Packet Structure and Parsing Approach

What is a Packet?

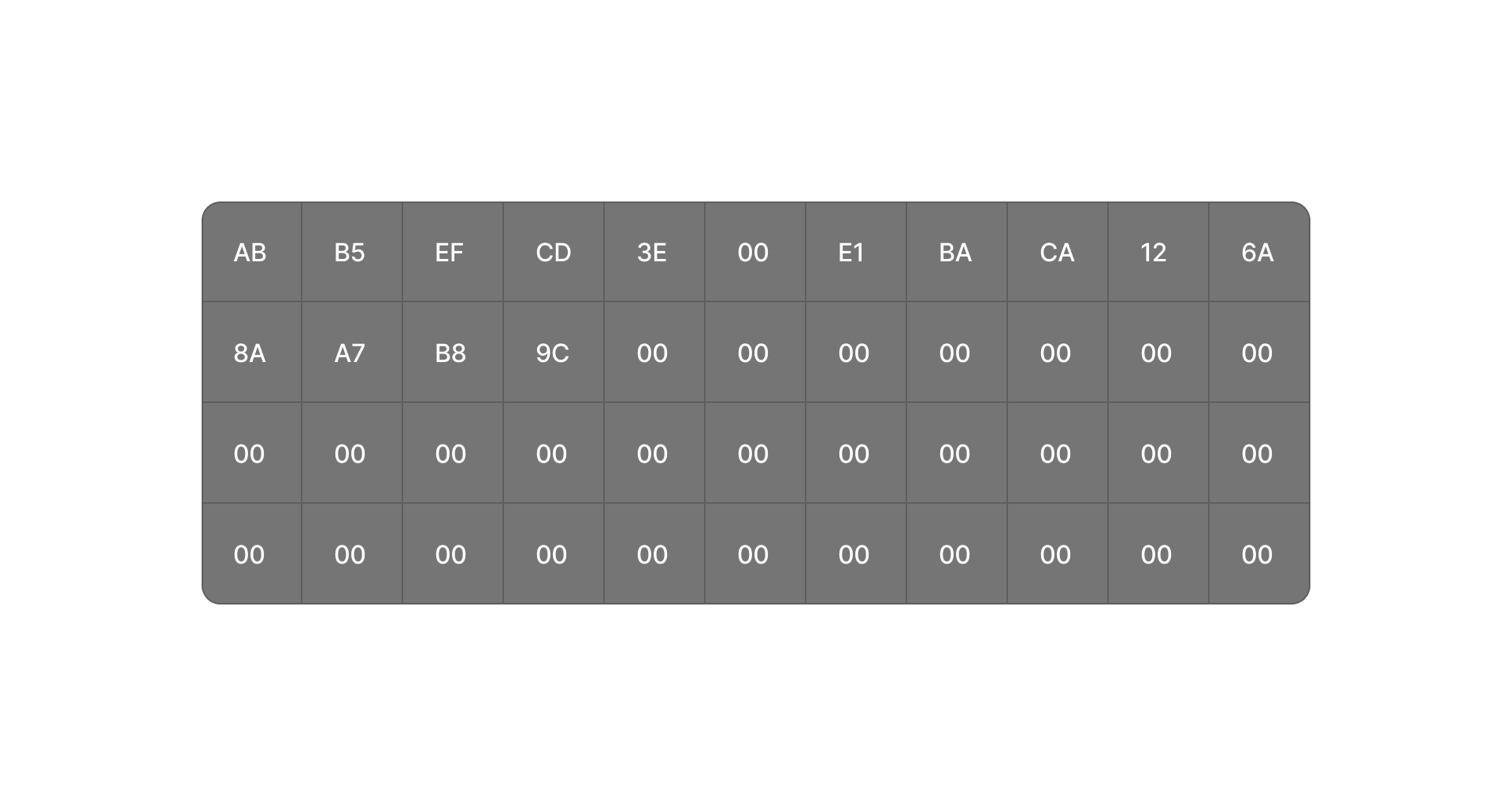

A network packet is a sequence of bytes transmitted over a network. Here’s an example of a raw packet in hexadecimal format:

A packet is essentially a list of bytes representing network data.

For example:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let packet: &[u8] = &[0x00, 0x11, 0x22, 0x33, 0x44, 0x55, /* other bytes */]; }

It is preferable to reference the packet (&[u8]) rather than copying it to avoid unnecessary memory usage and improve performance.

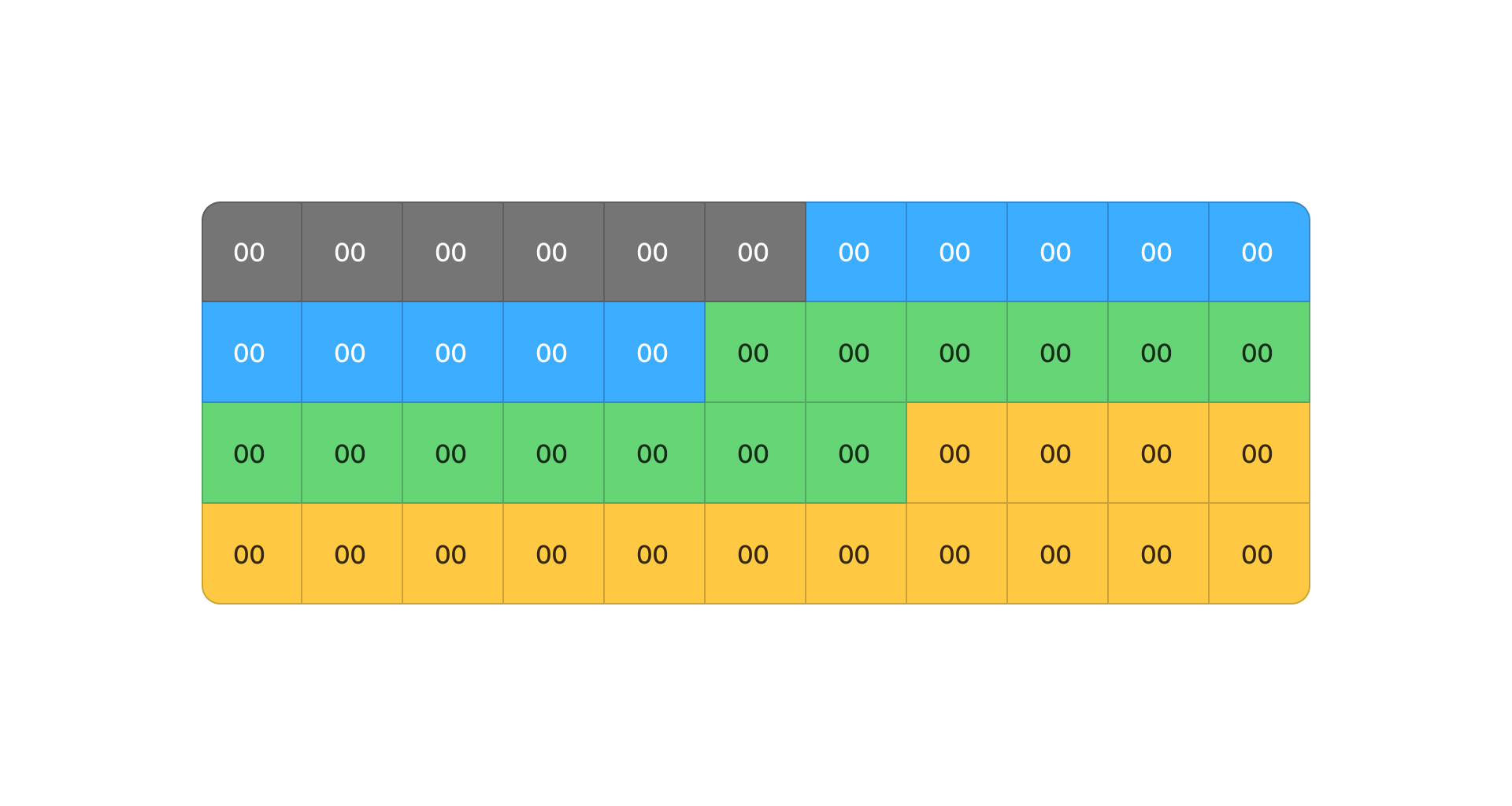

🎨 Identifying Protocols in the Packet

Each protocol occupies a specific part of the packet. By analyzing the bytes, we can identify different layers.

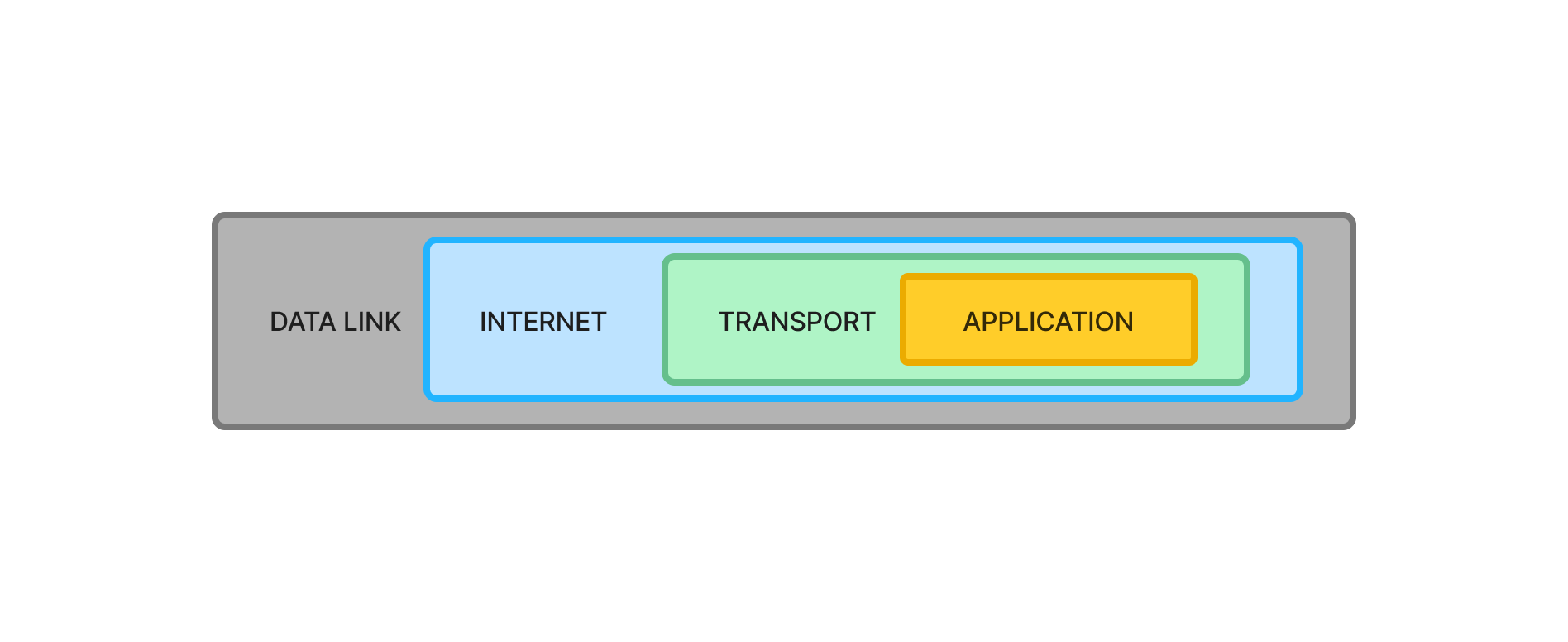

🪆 Protocols are Nested (Like Russian Dolls)

A network packet is structured as a series of encapsulated layers: each layer contains a protocol that encapsulates the next.

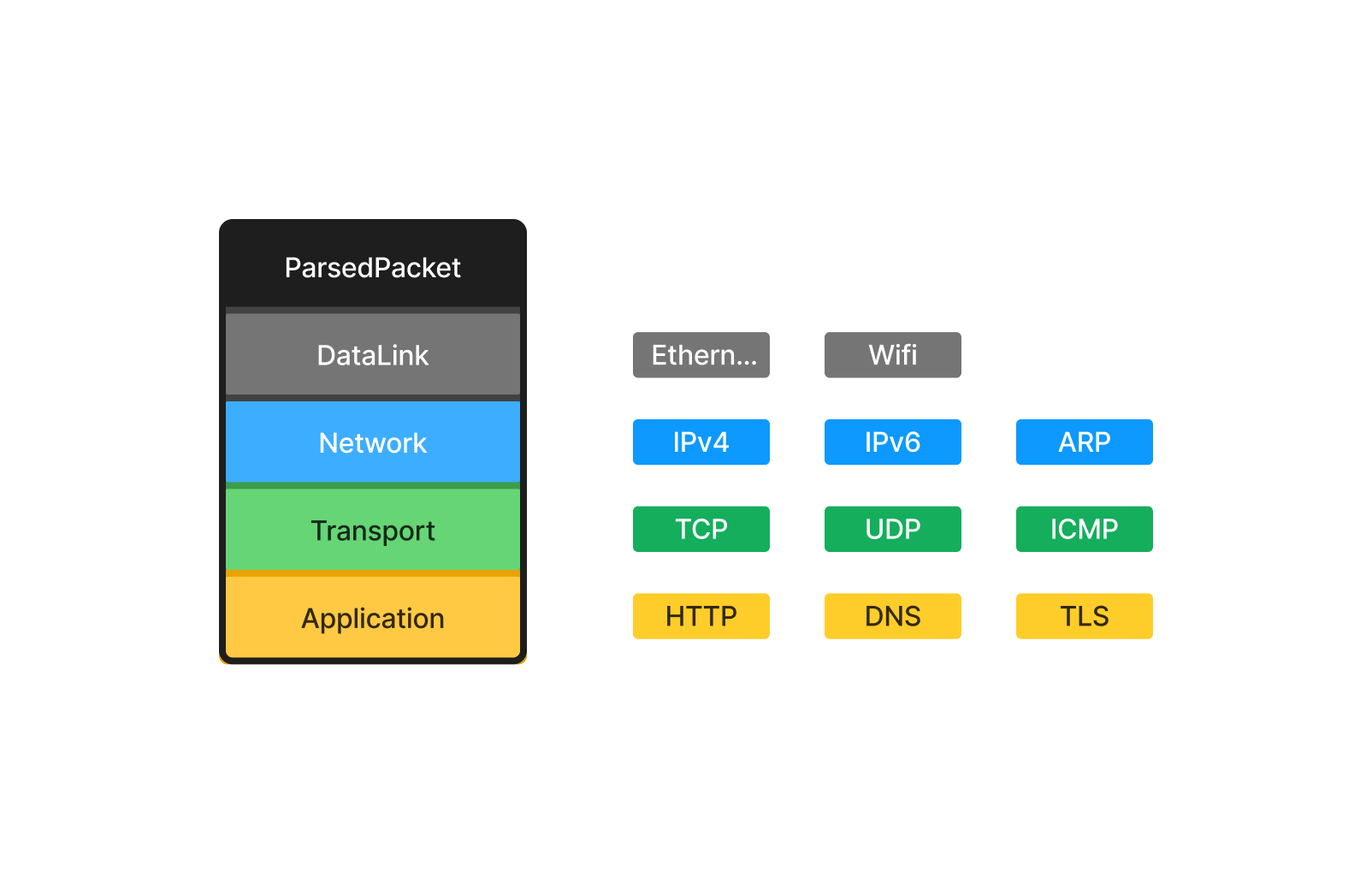

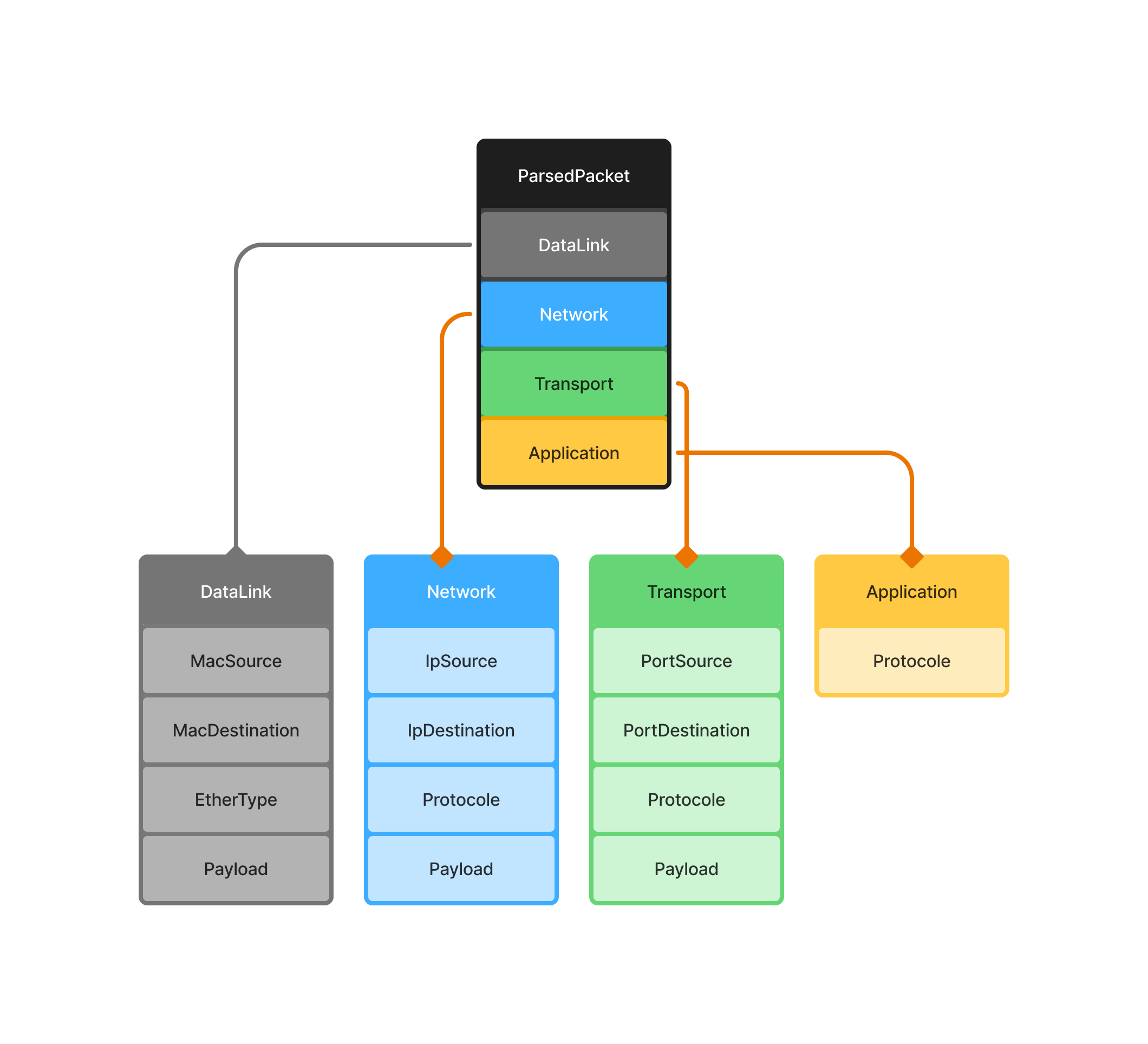

ParsedPacket Layered Structure

Once parsed, a packet is structured into four layers, following the OSI model:

The Data Link Layer is always present, while the others depend on the packet type.

🔗 How Layers Interact with Addresses and Entry/Exit Points

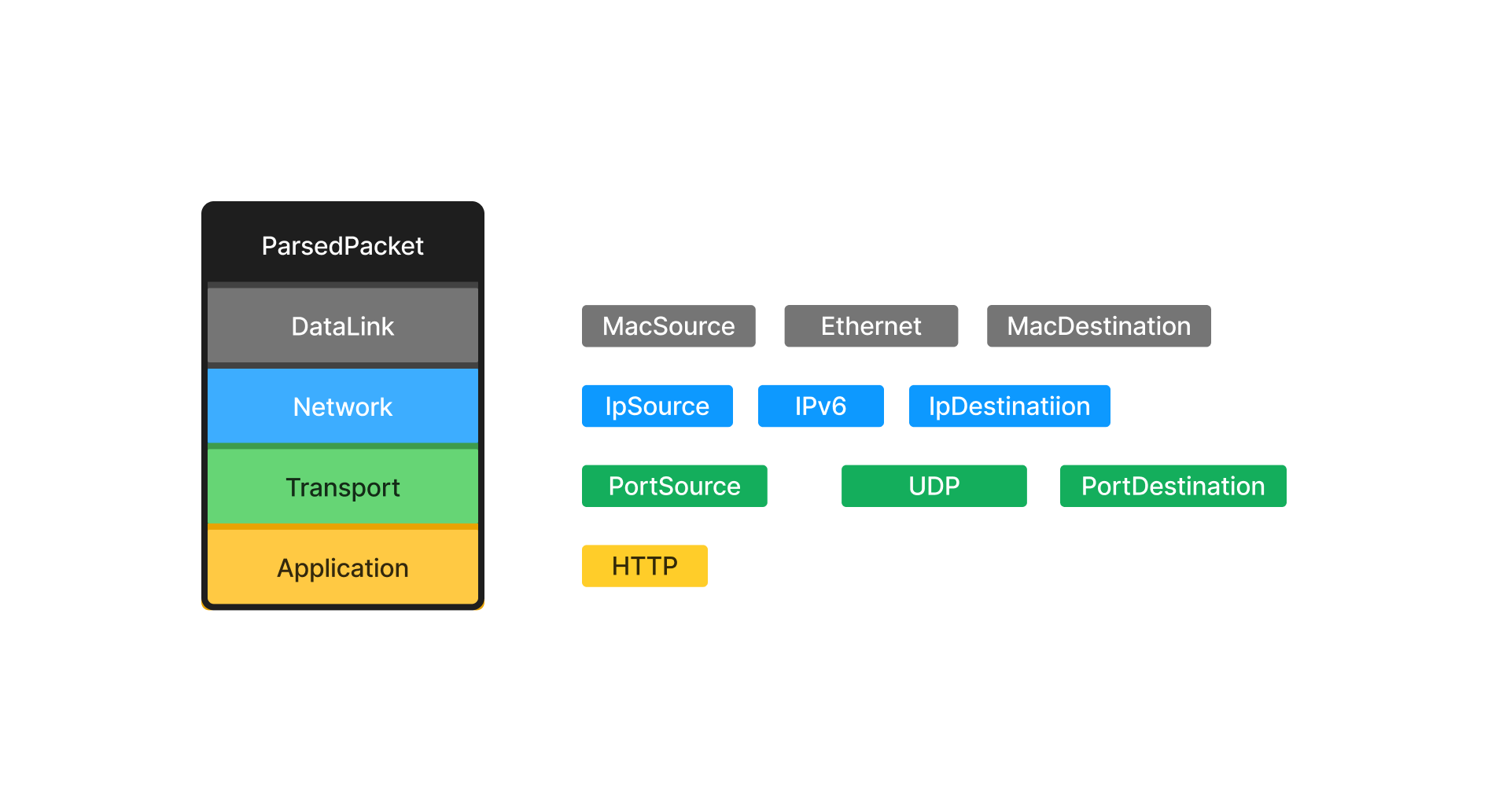

Each layer contains specific information to identify source and destination addresses.

🧐 Detailed Breakdown of Parsed Structures

Each protocol has its own structure with unique fields.

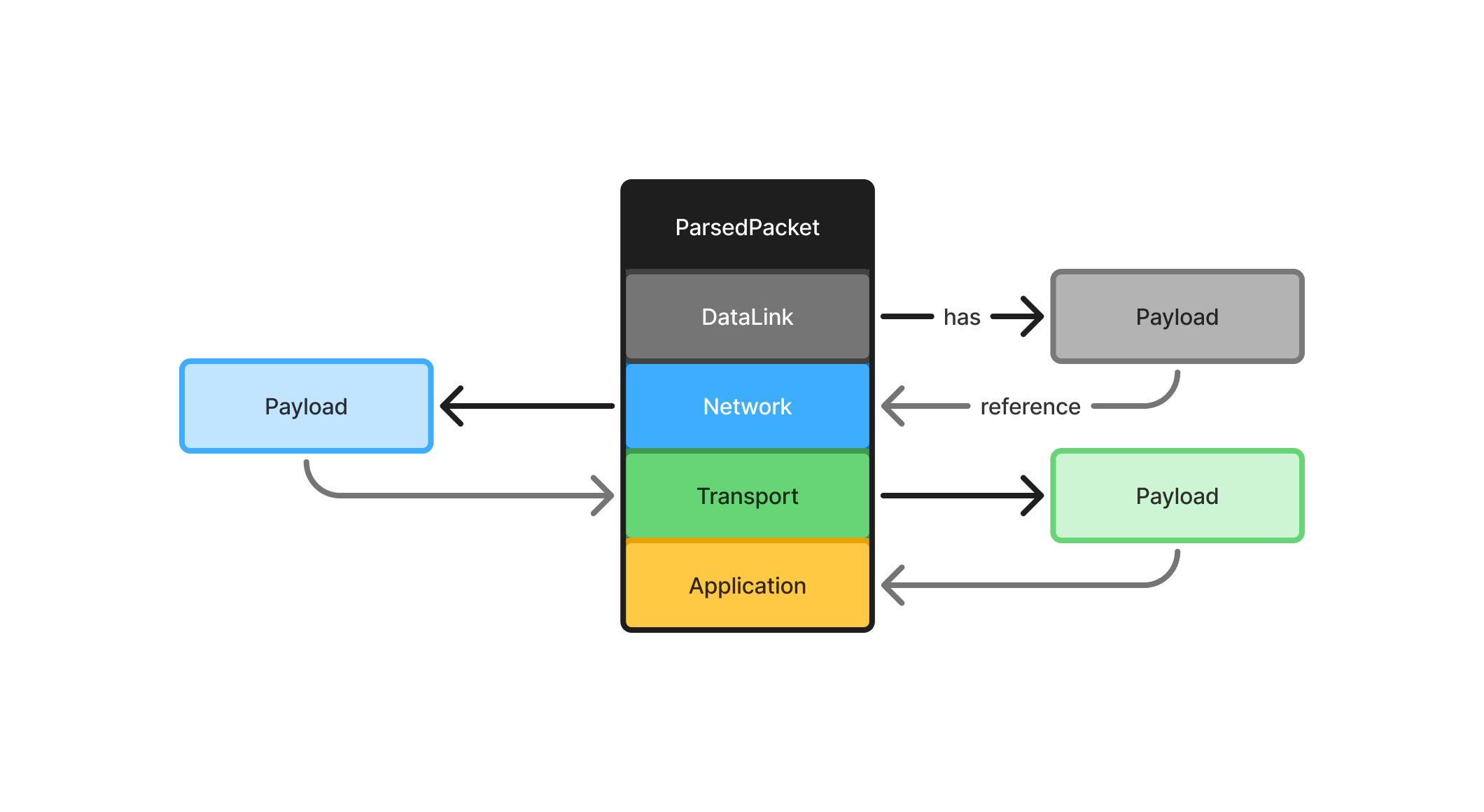

Parsing Strategy Based on Payloads

Parsing is determined by the payloads extracted at each stage.

Independent Layer Parsing

Each layer must be parsed independently from the others.

We do not use information from one layer to infer details about another.

Why?

- Security: Attackers can manipulate packet fields (e.g., changing port numbers).

- Flexibility: Some protocols do not strictly follow conventional port assignments.

- Reliability: Parsing should be based on raw data, not assumptions.

For example, we do not parse an application-layer protocol based on the transport-layer port number.

Just because a packet has port 80 does not mean it contains HTTP—it could be anything.